At 66m (215ft) it is cold and dark with an unexpected current

running. At this depth, too much physical exertion could lead to carbon

dioxide build up, convulsions and death, so instead of swimming, we

crawl along the bottom.

At 66m (215ft) it is cold and dark with an unexpected current

running. At this depth, too much physical exertion could lead to carbon

dioxide build up, convulsions and death, so instead of swimming, we

crawl along the bottom.

Inching across the ocean floor I control my breathing by reviewing

the long list of things that could go wrong on this dive, and then

mentally rehearse the required responses. Once more checking all the

valve positions, my thoughts drift to all the other times in my life

I've been crawling along in the

cold, dark, and wet.

| |

John and I go over a dive plan.

| |

This grim reverie is interrupted when my instructor taps my shoulder,

he's found a sea horse he wants to show me.

Kneeling on the bottom far beyond the recreational diving limits,

and watching this surreal little creature, the world seems to suddenly

come into a little bit better focus.

Down here, it seems self-evident the road less traveled is

always the more interesting, and that's really what technical diving

is about. In our ever shrinking and more traveled world it's another

way of seeking out stones still to be turned.

I've long wanted to take a course in trimix diving, but it

just isn't taught in many places. Since we'd done little research, it

was a surprise to find that not only does Sabang have a trimix instructor,

but a famous one. John Bennett currently holds the world record for the

deepest open water dive

(254m, 833ft) video.

- update:

-

On March 15, 2004, John was reported

missing presumed dead

after a commercial diving job in Korea. Obviously nothing I can say here

will make a difference in that, but, I would like to note, that over the

years I dove with a lot of people, some of the incredibly skilled. John

really stood out to me, not just for his talents in the water, but for

his willingess and ability to teach and share what he knew. The short bit

of time I got to study with him was precious, and the world is definitely

a little smaller without him in it.

We obviously won't be setting any records on my course, but it's

reassuring to learn these arcane skills from such an experienced

diver.

Deep diving is a delicate, and not entirely understood, balance

between the effects of breathing different gasses under pressure.

The air we normally breath is 21% oxygen, 79% nitrogen, and small

quantities of trace elements. In recreational diving, nitrogen is the

primary concern. As divers breath compressed air at depth, the

pressure forces extra nitrogen to dissolve into their bodies. This

excess nitrogen must be off-gassed as the diver ascends.

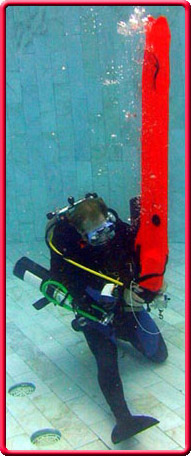

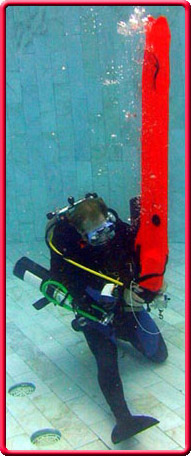

| |

|

Practicing with a surface marker buoy.

|

| |

If the ascent is slow enough, there are no problems, but if the diver

comes up too quickly the nitrogen can form bubbles that wreak havoc as

they lodge in joints or sensitive nerve tissue. This is

decompression sickness (DCS), or "the bends," and pain, paralysis,

and death are all possible consequences.

To extend the time they can remain at depth without unreasonably

increasing the risk of DCS, some divers reduce the amount of nitrogen

they breath by adding extra oxygen to their tanks making

nitrox.

But, breathing even normal air at 40m (130ft), the pressure makes the

body respond as if it was breathing 100% oxygen, and going deeper

oxygen toxicity becomes a significant threat.

Unlike DCS which often manifests subtly and only on the surface,

oxygen toxicity causes immediate and dramatic symptoms at depth. Most

common and worrying are convulsions, which cause the diver to

uncontrollably spit out his or her regulator and most likely drown.

An oxygen partial pressure of 1.6 atmospheres is the generally

accepted limit for technical diving and with air this partial pressure

is reached at 66m (215ft). To safely go deeper you need to breath a

gas mix containing less oxygen than normal air.

You could replace the oxygen with more nitrogen, but breathed at high

pressures nitrogen has a narcotic affect, and as tempting as it might

seem, deep dives are not best attempted with dull wits.

An inert gas is needed, and helium has become the most common choice.

With trimix, a blend of oxygen, nitrogen, and helium, the diver is

able to control his or her exposure to oxygen and reduce the narcotic

affect of nitrogen.

Helium doesn't have adverse affects until about 122m (400ft)

where high pressure neurological syndrome (HPNS) becomes a worry.

HPNS gives sudden personality changes, muscle tremors, and

convulsions, but 120m is deeper than I'm planning on going anytime

soon, so I'll worry about it later.

The final dive of my course is planned for 18 minutes at 80m (260ft).

The twin tanks on my back are filled with a mix of 14% oxygen, 40%

helium, and 46% nitrogen. In addition to the twins I carry a small

stage bottle under each arm. The left, lean mix, is 50% oxygen and

50% nitrogen, and then right, rich mix, is 100% oxygen.

|  |

| Geared up for trimix.

|

The mix of gasses in the main tanks is hypoxic, it does not contain

enough oxygen to breath on the surface, so I roll off the boat breathing from

the left stage bottle. At 15m (50ft) there is enough pressure to

breath from our main tanks so we pause our descent to switch gasses and

do a quick check for leaks.

The leak check is important because on our previous dives we have

meticulously measured my breathing rate and this dive has been

carefully planned to match my consumption. Despite the excitement of

going deeper than I ever have ever been before, I must breath slowly

and deeply, or we will have to turn the dive early to stay within our

safety margin.

Resuming our descent we quickly pass through the depths where the lean

mix, and even air would have been dangerous to breath.

Even if it weren't toxic, at our maximum depth of 80m (260ft), normal air

would have to be sucked from my regulator like syrup and the nitrogen

would be dangerously narcotic. The trimix though comes easily, and

my head is clear.

Despite the darkness and the cold, it's easy to imagine that we are far

shallower, but it's a dangerous illusion. At these pressures huge

amounts of nitrogen and helium are rapidly dissolving into my body. In

an uncontrolled ascent the bubbles formed by these gasses would almost

assuredly cripple, if not kill me. There is a hard ceiling above me, just

as assuredly as if we were in a wreck or cave.

Under these circumstances any problem is potentially catastrophic and

we train to deal with them instinctively. The equipment is reliable

and fully redundant, the diver is almost always the weakest link in the

system.

With time and gas checks, simulated equipment failures, and gawking

the occasional fish our 18 minutes of bottom time pass quickly.

Our first decompression stop is at 45m (146ft). On our way there from

the bottom, we are careful to maintain an ascent rate of 10m

(33ft) per minute. Helium is a fast gas and will quickly form

dangerous bubbles if we ascend too rapidly.

From here to the surface we'll do a decompression stop every 3m

(10ft). Drifting in open water as we are, it's difficult to maintain

such precise control of our buoyancy, so we deploy surface marker

buoys (balloons) to the surface, and hang off them by attached lines.

The first several stops are short, most of them just a minute, but

there is a lot to do. In addition to controlling our ascent rate and

getting the SMBs up we need to prepare for the gas switch at 21m

(69ft). I retrieve the regulator from where it's been stowed and turn

on the gas. The switch point is chosen to be just above the danger

level for the 50% mix. Breathing such a high partial pressure of

oxygen helps to flush the dissolved gasses out of my system and the

cumulative oxygen exposure is part of our dive plan.

The partial pressure of the 50% mix drops as we ascend through longer

and longer stops until at 6m (20ft), for our longest (27 minute) stop,

we switch to 100% oxygen at the maximum partial pressure of 1.6.

Hanging from my buoy, drifting through the seas with only plankton

for entertainment, I've got plenty of time to ponder the sense of

this kind of diving.

It's difficult, uncomfortable, hazardous, and intensive in gear and

training. All my favorite things, and they make for an inexorable pull

into depths ever less traveled.

|