The bureaucratic logistics of traveling in Tibet are notoriously

complicated. From Heinrich Herrer in 1939, to current day backpackers,

many a traveler has been turned back at a checkpoint. Independent

travel is actively discouraged by obfuscation of the rules steering daunted

visitors into easily controlled package tours. I've now been to Tibet, done

a bunch of things, and I still don't understand the system.

Stuart and I's main objective was Mt. Kailash in the remote western part of the

country. The mountain is the center of the universe for Tibetan Buddhists, and

a circuit, or kora, of its base is the most scared pilgrimage in Tibet.

The roads into the region are quite bad, but closely monitored by army

and police. When we went, truck drivers were being heavily penalized for

picking up tourists, so renting a Land Cruiser was the most common way of

getting there. Typical trips take about six people in a Land Cruiser with

an accompanying support truck. Facilities in the region are very limited

so often times these trips are set up as "luxury camping" expeditions

with a cook, etc...

Stuart and I opted for a more minimalist approach. For our price we

got a Land Cruiser, driver, guide, permits, and nothing else. We

were on our own to arrange food and accommodation throughout the trip,

although the tour company people helped us to get reasonable deals.

We arranged our trip in Kathmandu, but this was a mistake. It

would have been easier and cheaper to do it in Lhasa. For flexibility,

it's important to have an individual, non-group, Chinese visa. Despite

guidebook warnings that it might not be possible, we easily obtained these

in Kathmandu. The plane tickets on China Southwest Air, must be purchased

through a travel agent. What usually happens is that you buy a one-way group

tour to Lhasa that includes the flight, a night's lodging and transport

from the airport. Once in Lhasa you are on your own, and it's easy to

find like-minded travel partners in the guesthouses.

None of this is nearly as difficult as many people think (these

days at least), but remember, this is Tibet. Most roads are bad to begin with

and subject to flooding, avalanches, landslides, etc... Like the

weather, the politics and regulations are unstable. Our trip was very

late in the season and we traveled under the constant threat of being

stranded by a storm until who-knows-when. It's a place where anything can

happen, and often does.

- 14 Oct 1999

- The flight from Kathmandu to Kathmandu is one of the most spectacular

regularly scheduled flights in the world. Once free of Kathmandu's

smog, there are tremendous views out the left side of the plane as it

flies East up the South side of the Himalayas. At Mt. Everest, the pilot

practically plants the left wing tip on the summit as he or she executes a

sweeping turn leaving behind Nepal and entering Tibet, the roof of

the world.

Tibetan travel is infamous for being fraught with bureaucratic snarls

and we get our first taste at the airport. Technically, we are part of a

group, as you must be in order to purchase the plane tickets. Our

"group" is 20 or so people we've never met before, and the only thing we

have in common is that all our names are on a piece of paper proudly

proclaiming our grouphood. All our names that is except for two

unfortunate Swiss. It seems they'd added on only yesterday, and somehow

their names are not on the magic list. This is a major problem.

We all bake in the bus while the Swiss couple tries to work things out with the

Chinese immigration officials. As time went on, our group talked of

forming a pool to raise funds for the bribe that surely seemed our only way

out of the airport parking lot. In the end though, the Swiss, being

Swiss, would have none of that. They agreed to surrender their passports

and come back the next day for another round of "why our names aren't on

the list." A serious inconvenience, with the airport being nearly a

two-hour drive from town, but with the errant Swiss liberated, we started

down the road for... Lhasa, the forbidden city.

|

|

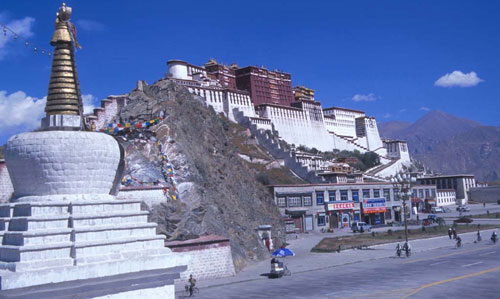

Tibetans getting some shade under the wing of a Chinese MiG

parked in front of the Potala Palace, one of Lhasa's most sacred

landmarks.

|

|

These days the forbidden city is replete with traffic lights and cell

phones, and on first impression, it's hard not to be disappointed.

Few travel destinations conjure up such images of mystique and remoteness

as does Lhasa, but in our ever shrinking world it at first seems just

another Asian city, maybe bit dirtier than most. Walking the streets, it

takes a while for Tibet's magic to hit Stuart and I.

After a year on the road, I'm used to being stared at, but the stares

in Tibet are different. The eyes don't call out, "hey, look at the

stranger" Instead, they seem to pour out a universal greeting, "Hello my

long lost friend, welcome to my home." On the streets of Lhasa these

wild eyes are accompanied by affectionate hugs and stuck-out tongues.

It would be days before we would learn that sticking out the tongue is a

traditional Tibetan way of showing that you are not a devil (they say the

devil can change all his appearance except his tongue).

I come back from our short stroll feeling refreshed and invigorated.

Tibetan's are people the way people are meant to be. Warm, welcoming and

always willing to laugh at a secret joke. I couldn't even make eye contact

without my new friends bursting out in laughter and running over to share

it with me. The laughter and good nature are contagious and I soon

found my cheeks cramped from smiling so much. Not a bad problem, as

problems go.

At 3,500m (12,480 ft), Lhasa is 2,250m (7,380 ft) higher than Kathmandu

and Stuart was feeling the effects of the change. So, with him

napping, I set out on my own for a longer walk around the Barkhor

circuit.

The Barkhor is the name for the neighborhood that surrounds the Jokhang,

Tibet's holiest religious temple. This is the heart of old Lhasa and

epicenter of Tibetan spirituality. The circuit around the alleys just

outside the Jokhang is Tibet's most popular kora, and many foreign

visitors first Tibetan experience.

Before reaching the kora though I have to run the gauntlet of antique, souvenir, and religious

paraphernalia shops that clog the Barkhor square.

This square has been the site for many of the demonstrations and

uprisings against the Chinese occupation, and it is now continuously

monitored by video cameras discretely perched on nearby rooftops.

Today all the cameras would record is the desperate struggle of a newly

arrived tourist to extract himself from the hugs, and overly friendly

grasps of jewelry merchants, their smiles redolent, their only words of

English, "I love you."

Through the blockade I join the human tide flowing around the Barkhor

kora. It's a mélange of Tibetan society, businesspeople on their lunch

hours, ragamuffin street urchins, and the sun-dried pilgrims who look as

if they've been doing this walk for thousands of years.

Everybody fondles beads or spins a handheld prayer wheel as they walk the

circuit intent on their own devotion, seemingly ignorant of the

surrounding shops selling everything from knockoff fur hats to industrial

hardware. The shop venders call out, the marchers mutter prayers and

from within Jokhang cymbals crash. The cloying scent of incense rides

heavy over the rotting garbage and the odor of dedication from the

pilgrims.

It's Tibet as I thought it might be, mystical, powerful, incongruously

profound amidst the discordant sights, sounds and smells. Feeling oddly

content I take up the chant that murmurs everywhere, Om Mani Padme Hum.

"Om Mani Padme Hum," it is the national mantra of Tibet, it fills prayer

wheels and flies on prayer flags, it's inscribed on rocks throughout the

country, and fills the heart of every Tibetan.

The simplest explanation I've found for it is that wisdom and compassion,

the jewels we should be seeking, are only to be found within us. Really

though, the mantra is meant to encompass the entire Buddhist spirit.

Tibetans believe that by reciting or invoking the mantra, you bring merit

and peace to the world. Circuits in temples are often lined with prayer

wheels. These are cylinders mounted on a spindle that can be spun by

hand. They range in size from a small coffee can to behemoths,

taller than a person, that require several devotees to set

in motion. Within the prayer wheels are long scrolls of paper inscribed with

the mantra and each clockwise revolution is said to invoke those

prayers.

Similarly, Tibetans adorn mountain passes, holy places, and even their

homes with prayer flags-- strings of brightly colored pieces of cloth

imprinted with scriptures. Each flutter of the flag releases the

blessing into the world.

Om Mani Padme Hum is the voice of Tibet. The low drone of its chanting

fills temples and echoes off high peaks while they as a people invoke

its power to calm the world.

Maybe we should all help a bit, chant it now, wherever you are, just for

a few minutes.

Om Mani Padme Hum, Om Mani Padme Hum, Om Mani Padme Hum...

|

|

For dinner Stuart and I chose the guidebook recommended Tashi-I.

Through a door on the street that seemed as likely to lead to a carpet factory

as a restaurant we climbed a decrepit flight of stairs, mercifully dark,

and found ourselves in the midst of a continual celebration over the joy of

being in Tibet.

The place is run by two ebullient young Tibetan girls and their weary but warm

mother. The girls would flit about, pulling each other's hair, cavorting with

customers and occasionally bringing out a dish or two. Their mother vainly

tried to maintain order, making sure food eventually did arrive and

dealing with the more vexatious language problems.

Submitting our orders, we came to the attention of the girls. They were

immediately taken by the thick blond hair on my arms, pawing it as if

grooming an errant pet. Caught up in their mischievous mood I pulled up

my shirt and showed them how far the fur extends. I was instantly

dubbed "yak boy" and the name would stay with me throughout the country

as Tibetans kept discovering a fascination with blond body hair. Stuart

was labeled "chicken boy" after the dish he ordered, and in the nights

we returned it would always greeted, "Ahh, Yak-boy, Chicken-boy, welcome!"

The food here was the best we had in Tibet, yak and veggie momos

(dumplings) served with a hot sauce followed by Tibetan spiced chicken

stir fried and served with thin pancakes. To my palate the Tibetan

flavors seemed a mix of about 70% Indian tastes and 30% Chinese. Richly

spiced, but not that hot. As the food choices dwindled on the road to

Kailash, we would greatly miss Tashi-I.

We kept coming back though, not just for the food, but for the

atmosphere. The place has a welcoming spirit fueled by the family's

frenetic energy. After only a few days we felt like old friends even

though our conversations were mostly food items and gestures.

Each night as the crowd thinned, they'd sit down with us and a Tibetan phrase

book and we'd all try to learn a few new words as Stuart entertained them with

his tongue piercing and magic tricks.

|

Who is Stuart?

Stuart Wild: aka Wild Stu and known throughout Tibet as Chicken Boy.

|

|

|

Helicopter pilot, yacht crew, ski pro, scuba instructor, prestidigitator, and

50-year-old Indian movie star look-alike Stuart knows how to get out there, and

was a perfect partner for the trip to Mt. Kailash.

We met in a karmic moment as we were both sat in the Bahrain airport

waiting for a flight and I overheard him talking about Western Tibet.

We spent a few days raising a ruckus in Kathmandu, and then were off

together for three weeks in Tibet.

My only regret about doing this trip with Stuart is that we never found a

Chinese helicopter for him to steal. Rats!

|

|

|

- 15 Oct 1999

- Stuart was still feeling down from the effects of altitude, so I again went

out on my own to explore more of Lhasa.

First stop was the local Internet cafe! While painfully slow, I did manage to

read all my new messages, and the irony of sending email from the

forbidden city was not lost on me. It may not be quite as good as it

sounds though. Rumors here abound about the Chinese government

monitoring e-mail and arresting people based on it's content. I'm

familiar enough with the workings of the web (my old resume) to know what a difficult task

that would be, but as a believer pointed out, the Chinese are not short

on either motivation or human resources.

Dwelling on the old and new, I went for a walk searching for the Lhasa of yore,

but instead found only a modern bustling Chinese city. The Tibetan district is

small, focused around the Barkhor and seeming only to be about 20% of the city.

The rest could as easily be Chengdu or any other small ratty Chinese

city. Across the main street from Dalai Lama's old palace,

the Potala,

is an open, "People's Square" with Chinese military hardware on

display. Alongside that is a used car lot. Disheartened I returned to the

Barkhor to explore it's interior temple, the Jokhang. Inside, were

pleasant surprises, a puja (prayer service) in progress and two

friendly Spanish women I'd met on the plane.

|

|

A puja underway in the Jokhang.

|

|

Together we took in the dissonance of a Tibetan prayer ceremony. Groups

of monks chanted prayers from ancient books. Their voices seemed to roll

like waves, each group rising to a different crescendo and then

occasionally all coming together and breaking with crash. They chanted

in a deep, low, monotone and to my untrained ear the result was more like

that of a gentle percussion instrument than of the human voice.

At points they'd be joined -- or interrupted, it was hard to tell -- by the

real drums. Double sided drums the size of car tires, set on poles and beaten

with crazily curved mallets.

Hrum, rmm, rmm, dra, ya', yum. Hrum, rmm, rmm, dra, ya', yum. The monks

voices would murmur at a rushed tempo and Bromm, Bromm the drums would

intervene at an unhurried pace.

The trumpets were the final voice in this cacophony. Thin slender

trumpets half again longer then a person and with sound like a wounded

animal, a very large, very angry and mortally wounded animal.

Braamfffff they'd shrill to the delight of the Tibetans and

drowning out any other sound.

A puja doesn't have the solemnity of a western religious service. Young

monks tell jokes, pinch each other and occasionally deliver a whack with

their prayer books. Tibetans wandered through the monks to make

offerings with seemingly little care to decorum.

For we, the uninitiated, it was difficult to make sense of, and there was

no one around to ask. I think the focus of this ceremony was monks

in the background making tormas, barley flour cakes decorated with

colored yak butter, and all the rituals were to consecrate them for

future offerings.

But even blind to the meaning, there was a sense of energy in the

gathering. Wizened old pilgrims drifted in, faces browned and deeply

creased by years in Tibet's harsh climate, they looked as if they just

as easily be a 1,000 years old as the 50. They probably were. Poised

before the rows monks and performing ritual prostrations and I saw tears

in the eyes of at least one as she turned and made her way out.

- 16 Oct 1999

-

While the Barkhor is truly Lhasa's heart, the Potala is surely its crown.

No other landmark is as indelibly associated with Tibet and its plight

as is the Potala Palace, rightful home of the Dalai Lama.

Historians say that 7th century Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo was the first to

build a palace on this site, but it was the great fifth Dalai Lama in 1654 who

began work on the Potala we see today.

With 13 stories providing 130,000 sq. meters of floor space it is a massive

structure that captures the imagination. Visible from all over the city the

Potala dominates Lhasa and is a constant reminder of what is, and what might

be.

Traditionally the home of the Dalai Lamas, the Potala is now a tourist

attraction, and today Stuart and I went on the tour. Inside it seems more

a temple than a palace. Chapel after chapel filled to overflowing with Buddhist

scrolls, paintings, statues and altars. It even contains tombs for the Dalai

Lamas, the most impressive being that of the great fifth. His funerary stupa is

over 12m (40 ft) tall, is gilded with 3,721kg (8,223 lbs) of gold and decorated

with 15,000 pearls and gems.

Each twist and turn through the three-dimensional maze of the Potala reveals

similar treasures, but for me the most profound sight was also one of the

most unassuming.

Turning from the roof into a set of small chambers you find the private

quarters of the 14th and current Dalai Lama. His personal effects are laid out

at his bedside as if he might return at any moment.

Although it was really from

Norbulingka, the summer palace, that he escaped in 1959, his presence in this

room is strong. I got the sense that some aspect of time has stood still here

as if even that immutable force awaits His Holiness's return.

After our tour through the Potala, Stuart and I went by our travel agency

to get a guide to help us with our shopping. With his assistance,

provisioning for the trip was easy. No haggling, no rip-offs, our guide

took care of the negotiations and we just walked through stores,

pointing at cases of Coke, cookies, and instant noodles. These would be

our staples on the long road to Kailash.

For dinner we returned once again to Tashi-I, this time with Catherine, a

Chinese born woman residing in New York, but on a trip through Russia,

China, Bhutan, and Tibet.

Dinner with Catherine was fascinating. As well as planting the seeds for

eventual trips to Bhutan and Mongolia, she challenged my pat Western notions

of China's villainy in Tibet by providing the Chinese taught version of

things.

| Tibet |

|

China |

|

-vs- |

|

|

When the iron bird flies and horses run on wheels,

the Tibetan people will be scattered throughout he world

and the Dharma will come to the land of red men.

|

--Guru Rinpoche, 8th century establisher of Buddhism in Tibet.

|

|

Chinese claims to Tibetan sovereignty stem from an expedition by

Emperor Kang in 1720. He entered Lhasa with a military force and drove out the

Mongols who'd been occupying Tibet for three years. Kang Xi brought with

him the

7th Dalai Lama, who'd been held by the Chinese for years. Between driving out

the Mongols and returning the Dalai Lama, Kang Xi was greeted as a hero even as

he declared Tibet a Chinese protectorate.

The Manchus ruled Tibet for nearly 200 years, responding with an iron fist to

any insurrection. The rest of the world snuck up on their isolationism though

and in 1903, the British, led by Sir Francis Younghusband, invaded. The

British were concerned about Russian expansionism and wanted to secure

Tibet as a buffer to their colony, India.

Younghousband's force of 1,000 well-armed men met the Tibetan army of 1,500 near

Gyantse. The Tibetan's were equipped primarily with swords and their secret

weapon: charms bearing the seal of the Dalai Lama that the monks assured

them would be protection against British bullets. As the British

attempted negotiations, a false alarm was raised and 700 Tibetans were

killed in four minutes.

Younghusband advanced on Lhasa only to find the Dalai Lama had fled to

Mongolia. He negotiated a treaty with the regent, but the Manchus

objected and in 1906 the British, in a move to block Russian advances,

signed a treaty with the Manchus acknowledging the Chinese right to rule

Tibet. In 1910 the Manchus decided to make good on the promises of this

treaty and invaded Tibet, sending the Dalai Lama fleeing again, this time

to India.

A 1911 revolution toppled the Qing dynasty in China, and in 1914 the 13th

Dalai Lama returned to a liberated Tibet and enjoyed almost 40 years of

self-rule. The 13th Dalai Lama traveled to the west and realized that

Tibet must modernize its infrastructure and social systems to survive in

a modern world. His reforms were met with great resistance in

traditionally isolationist Tibet.

His efforts mattered little though because in 1948 Mao Tse-tung took control of

China and on October 7, 1950 30,000 Chinese troops invaded Tibet and

quickly overwhelmed the Tibetan army of 4,000.

In Lhasa, the 15-year-old 14th and current Dalai Lama was quickly enthroned so

that he could assume command of the county. Knowing that Tibet could not stand

against Chinese aggression he dispatched a delegation to Beijing to negotiate.

As it turned out, no negotiations were required, as the Chinese had already

drafted the 17 point, Agreement on Measures for the Peaceful

Liberation of Tibet, and even forged the Dalai Lama's seal for it's

ratification.

The document ceded control of Tibet to China in exchange for

unenforceable guarantees about the Tibetan way of life. The Dalai Lama's

delegation acknowledged they had no authority to sign such a document,

and the Dalai Lama himself opposed it when he finally got a chance to see

it. But, the Chinese touted it as the peaceful liberation of the Tibetan

people from years of serfdom to the monks and religious state.

Tensions built between the Chinese invaders and the Tibetans until things came

to a boil in 1959. The Dalai Lama was commanded to attend a New Years dance

without his usual contingent of bodyguards. Word of this leaked and 100s of

Tibetans surrounded the Norbulingka palace promising to protect the Dalai Lama

with their lives.

On the streets, Tibetan Soldiers shed their PLA uniforms and the strain

finally reached a breaking point as shells began falling on the palace

grounds. It became clear that no peaceful solution was in the offing

and on March 17, the Dalai Lama fled to exile in India. On March 20,

more violence broke out and estimates are that in 3 days, 10,000 to

15,000 Tibetans were killed.

With the Dalai Lama in exile the Chinese began the wholesale destruction of the

Tibetan way of life. Buddhism was banned with monks and nuns tortured and

brainwashed. By the end of the 1966-1976 excuse for genocidal insanity in

China, the so-called Cultural Revolution, only eight monasteries had

escaped destruction (out of literally thousands).

Amnesty International and other organizations estimate the Chinese have killed

over 1.2 million Tibetans (1/6th the population) in the course of the

occupation. But almost worse is the policy of relocating (sometimes forcibly)

Han Chinese to Tibet. There is no reliable census data, but simple observation

shows that the Tibetans are close to becoming a minority in their own country.

In 1972 the restrictions on worship were lifted, and even some Chinese

officials now acknowledge the excess. But it is an absolutely tragic

situation and an ancient and mystical way of life is on the verge of

extinction.

Many have written far more passionately and eloquently than I ever could, I

encourage you to visit these web sites to learn what *you* can do to help:

- Tibet Online

- Lots of information, find your local Tibet Support Group!

- Government of Tibet In Exile

- Official site of the Dalai Lama.

- Tibetan centre for Human Rights and Democracy

- Investigating human rights abuses in Tibet.

|

|

|

- 17 Oct 1999

-

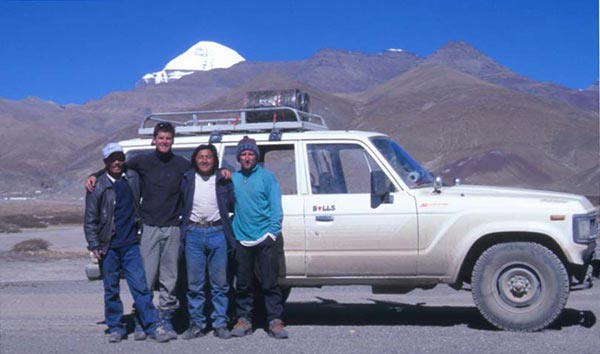

At 8 a.m. our guide, Pasang, and driver, Lakbha, picked us up in the Land

Cruiser and we made first acquaintances with our family and home for the

next 2 1/2 weeks. After loading it full of our supplies we piled in

and headed down the road out of Lhasa.

|

|

Left to right: Lakbha, Stuart, Pasang and myself.

Front to back: Us, the Land Cruiser and Kailash.

|

|

We drove out down the Brahmaputra River, and then as the pavement ended,

we began the long series of switchbacks to the 4,997m (16,390 ft)

Kamba-La pass. From the pass we looked down on the "scorpion shaped"

Yamdrok-tso lake 500m (1,500 ft) below. To my eyes, the lake, one of four

holy lakes in Tibet, looked more like a vine, with beautiful turquoise

and jade tendrils reaching up into the mountain valleys.

The road descended to the lake and then hugged its north and west shores

before rising again to cross the Karo-la pass. At 5,045m (16,547 ft) we are

more than 200m higher than Mt Blanc in Europe and more than 2,300 ft

above Mt. Whitney in the United States, but still on the main

highway in Tibet.

Our destination today is Gyantse, a town our guidebook advertises as one of the

least Chinese influenced in Tibet. Sad if true, because to us it appeared at

least a third if not half Chinese. The town sits nestled between a

monastery complex and a ruined dzong (fort).

The Gyantse Dzong is an imposing structure built into the summit of a hill

looming above the town. It has a thick, heavy, medievally impenetrable look

to it and even today in it's dilapidated state it seems able to repel any

invaders. In point of fact though, in 1903 it took just one day to succumb to

an attack of British soldiers led by

Sir Francis Younghusband.

Things were quieter the day we were there though. A pack of dogs, a

few cows and some Tibetan children playing ball were all I found on the

streets as I took an evening walk getting my first feel for life in Tibet

outside of Lhasa.

- 18 Oct 1999

- This morning we visited Pelkor Chode Monastery complex at the back of

Gyantse town. The highlight of the compound is the magnificent Gyantse

Kumbum. The Kumbum is a multi-tiered, wedding cake like structure that

is topped by a gold dome. It's visited by ascending it in a spiral. You

climb the steps to a new floor, walk around clockwise studying the murals

in the temples, and then ascend to the next floor. Each floor has

several chapels, each with several murals and an alter. There is a lot

to see, but to the untrained eye it all quickly seems the same.

Much more interesting for me was to watch the pilgrims. In town, they

buy slabs of butter for their visits to the Kumbum. At each alter they'd

spoon a chunk of their butter out into a tub as an offering. The monks

then collect the butter and use it to fuel the hundreds of devotional

candles that adorn each chapel. The steps joining the floors in

Kumbum are really ladders. Steep, rickety affairs rough hewn from logs

and poorly lit. The pilgrims, many old folks past their best climbing

days, would struggle up these ladders carrying their butter packets.

They often seemed ready to fall, but hands from above and below would

steady them and pull them through to the next floor.

You see this sort of devotion all over Tibet, people with little to eat

making offerings of rice and taking what seems like their last tired

steps in acts of pilgrimage. The practice and rituals of Buddhism are

an indelible part of the Tibetan culture.

Finished in the Kumbum we made the short drive to Shigatse, the second largest

town in Tibet. Shigatse is also a major stop on the tourist trail from

Lhasa to the Nepal border on the so called, Friendship Highway. The hotel was

chock full of travelers in the midst of various programs. Some were doing

standard package tours and others, more adventurous mountain bike trips.

Relaxing on our sun-deck and later eating dinner with the other

foreigners I felt very "in here" and not, "out there."

In the afternoon, Pasang took us on a tour of Tashilhunpo Monastery.

The largest functioning monastery in Tibet today and historically a very

important one, Tashilhunpo is an interesting place. But, word of mouth

and guidebooks both say that all seen here must be treated with caution.

The monastery is also the seat of the Chinese effort to subvert Buddhism,

and rumors abound of monks asking tourists for Dalai Lama pictures (both

prized and illegal in Tibet), and the generous/foolish tourists then

receiving a police visit that night. Some even go so far as to say that

all the monks here are in the pay of the Chinese and that the entire

complex is a sham left in place just to entertain tourists.

Nonetheless, Tashilhunpo was mostly undamaged in the Cultural Revolution and

it's temples make fascinating viewing. Pasang accompanied us to

explain the imagery and despite his not really being fluent in English,

we soon had a crowd of hangers-on listening to his explanations.

Tashilhunpo is a big place and Buddhist iconography is a long and complicated

topic, but I'll include here one popular example. According to

Pasang, the multi-headed, thousand armed image that seems so popular in comic

representations of Buddhist art is Avakokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of

Compassion from whom the Dalai Lama is said to be reincarnated. He has

so many heads because his is said to have exploded when he contemplated

all the ills in the world, and he has a thousand arms because that is

what it will take to cure those ills.

Our tour ended at the tomb of the 10th Panchen Lama.

- 19 Oct 1999

- While I was in Kathmandu, an e-mail friend from Scotland had sent me

the book, Walking to the Mountain. Written by Wendy Teasdill, it is her account of

how in 1988, with the area officially closed, she had rode, hitched, and finally

walked this route from Shigatse to Kailash.

As we pulled out of town I sat in the back of our comfy Land Cruiser and

read how Chinese officials foiled her attempts to buy a horse in

Shigatse, so she had stocked up as many supplies as she could just barely

carry and staggered down the road we were then cruising at a comfortable

clip. About 20k outside of Shigatse my place in the book and physical

location intersected, but the connection was tenuous. As I read about her

begging matches off pilgrims and struggling across swollen rivers I'm

overcome by a sense of normalcy and being "on the beaten path." I pondered

this for a long while and begin hatching schemes to banish those feelings.

Tonight's town, Lhatse, typifies the Chinese presence in Tibet. A long row

of sterile, box-like buildings faced with white tile and blue glass. The town

looks more like the inside of an airport bathroom than a Tibetan village.

The restaurants are all Chinese so we dine on fried noodles and go to bed

ignoring the lure of the flashing lights at the Karaoke/disco place across the

street.

- 20 Oct 1999

-

As we rolled out of Lhatse, the "road" turned quite literally into a

streambed, and for the first time I began to feel a bit off the beaten

track. Lakbha turned out to be a fabulous driver and he deftly maneuvered

the Land Cruiser around boulders and through innumerable river

crossings. They are building a new road here, on the banks above the

river, and I wondered what the journey will be like in a few years.

As a traveler, I am both a victim of and a participant in this

process. Each time down a road it shifts just a little bit from "less

traveled" to "more traveled" and will never quite be the same for those

who follow. Sad in a way, that it is impossible to share those perfect

moments in both time and place.

My sense of contentment with our own level of adventure was short lived though.

As the day wore on dark clouds gathered and it finally began to snow.

As we finally left the stream bed and began climbing for a pass we met a jeep

full of Chinese police and a parade of trucks that all had been turned

back. It had been snowing hard higher up and the road was treacherous.

Just as our trip had been getting interesting, it seemed it might be over.

The guys don't want to risk a try at the pass, and for the first time we

heard what would become their stock excuse, a concern over fuel, in

convincing us to return to the previous town and spend the night.

And so, midday found us in Sangsang without much to do. In our

frustration we hiked up a peak just outside of town and dubbed it

Mt. Disappointment.

|

|

|

Footbridge near Mt. Disappointment.

|

|

- 21 Oct 1999

-

|

|

The usual means of transport in Western Tibet.

The Swastika was an ancient symbol for good luck long before Hitler took and

interest in it.

|

|

|

|

We had been hoping for news of someone crossing the pass from the other

direction, but with no signs of any successes we (and everyone else) set out to

give it a go.

As we drove, we passed more bad omens, several trucks still stuck where

they had obviously stopped and spent the night. There really wasn't that

much snow, less than a foot, and both Stuart and I were incredulous that

here in the "Land of Snows" they'd never heard of tire chains.

As the road steepened we lost traction and went skidding back down.

Lakbha sent Pasang out to lock the hubs into 4wd as Stuart and I again

slapped our foreheads. We had assumed we'd been in 4wd for days now.

With the hubs locked we managed that and came to the scariest bit.

The one lane road there was built precariously into the side of the cliff

and the ice-choked river roared several jeep lengths below us. As the

tires began to slip and we slid closer and closer to the precipice I saw

Lakbha take one hand off the wheel in a Buddhist prayer gesture just as

the wheels regripped and we lurched over the hill.

A bit later we came across the Chinese police walking, afraid to ride in

their jeep. Obviously not enough prayer...

Over the pass things got easier and we soon pulled onto the high Tibetan

plateau, the dry barren wasteland that makes up most of Western Tibet.

We stopped in the town of Saga, ostensibly for gas, but the guys

disappeared so I went for a walk.

Sirens sounded and a voice began to blare through a loudspeaker. It seemed for

all the world like a town-wide fire drill as people began to line up and march

down the main street. At the end of the street was a large official building

flying a large Chinese flag from a tall pole, On the building's steps a podium

had been set up and before it stood a Tibetan man with his hands cuffed behind

his back. For 15 minutes at the podium, an official ranted at the gathered

crowd and then the man was taken away.

To this day I have no idea what it was all about, and it may not have been

nearly as sinister as it looked. The experience shook me though, and I was

embarrassed that my camera remained in its bag and I didn't even ask any

questions.

Stuart and I eventually discovered the guys tucked in a video room behind a

restaurant. They had been watching a kung-fu movie and thought it was now too

late in the day to go on. We were having none of it though, and anxious to

make up for the lost day forced them out into the sun and back on the road.

After another few hours of driving we stopped in Zhongba, our smallest town yet.

Tibetan Hospitality

This town is typical of many in the region, a few traditional Tibetan homes

and a guesthouse nestled in a bend of the road. The buildings all have walled

courtyards, and these courtyards are the de facto toilets. When

asked where we should properly do that sort of business, Pasang responded

with a sweep of his arm and joyfully pronounced, "anywhere."

The buildings are whitewashed, and then topped with a band of

Burgundy. Atop the walls are drying stacks of yak dung, the ubiquitous

fuel in this region. For dinner, we step over a knee-high doorsill and

join our hosts in their living quarters.

There is no electricity, and kerosene lamps dimly light the room. Smoke

from the yak dung stove blends with smoke from the endless cigarettes and

swirls about the low roof. The roof is supported by rough-hewn beams, painted

in the Tibetan style of intricate swirls and filigree done in bright primary

colors.

Lying in the corner on the dirt floor is a days-old sheep carcass. Our host

walks over and using the dagger from his belt hacks off a few pieces of

raw meat -- Tibetan snacks. Their staple is tsampa, barley flour mixed

with yak butter and water to make a doughy paste. We tried a bit and

found it tasted a lot like sand so instead of raw sheep and tsampa

we opt for thukba, Tibetan noodle soup.

The woman of the house mixes flour and water, then rolls out our noodles by

hand, taking breaks to add more yak dung to the stove, also by hand. A pot of

water is brought to a boil and the noodle chunks are tossed in along with some

wilted cabbage and a dash of soy sauce. This is thukba, our staple for

the time we were in Western Tibet. While it boiled our cook picked up a

bottomless toddler and spread his legs for him to pee on the dirt

floor of the kitchen cum living room cum bedroom. Dust control?

Our thukba is served with bö cha, Tibetan yak butter tea.

The tea comes from a churn where hot water, rancid yak butter, and a

handful of spices have been blended. Note the decided lack of tea in

"Tibetan yak butter tea." The potion isn't really as vile as it sounds,

especially here where the people are poor and skimp on the butter. It

tastes mostly like fatty salt water with lingering flavor of old leather

shoes.

The biggest problem with bö cha is the never-ending supply of

it. The tea is a mainstay of Tibetan hospitality, and a cup is instantly

poured for anyone who enters a home. It's not really possible to refuse

or to avoid drinking. Every few minutes the host makes a round of the

room proffering each guest his or her cup and a sip must be taken.

Finishing a cup is an impossibility as when even a fraction of millimeter

is sipped off, the cup is immediately refilled from a seemingly endless

supply. Keeping the cup full is a matter of pride for the host.

The game becomes one of drinking just enough that the refills keep our cups

warm (perish even the thought of drinking cold bö cha!), but not so

much as to turn our western stomachs. A difficult balance.

|

|

|

|

- 22 Oct 1999

- The drive along the high plateau is nothing like what I expected.

Vegetation and signs of life fade as we encounter sand dunes blocking the road

and it feels more like

Egypt

than Tibet.

The only sign of snow is atop the 7,000+ meter peaks of the Annapurna range that

tower off the plateau to the South. Walking barefoot in the sand it almost

feels like a beach and it's a surreal juxtaposition to be staring

out at some of the tallest and most famous mountains in the world.

|

|

|

Stuart walking on sand dunes in Western Tibet. Just out of view to the left is

the Annapurna range of mountains.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Temple entrance adorned with yak skulls.

|

|

|

The day's drive brought us to Paryang, a squalid little place whose primary

feature was a huge trash pile in the middle of town. Like most towns in Western

Tibet this one is inhabited by a pack of wild dogs. At the sound of something

new being tossed onto the garbage pile they'd come running from every corner

and viciously battle for the title, "king of the mountain."

The town's other point of interest was a Buddhist temple containing a huge prayer

wheel. As we watched, wizened old women dressed in Traditional Tibetan garb and

mountaineering goggles would stagger into the temple and spin the wheel. Twice

as tall as them and far heavier they'd grab it together and throw their backs

into it setting it in motion for a few minutes and releasing more prayers to

the world.

Outside the temple entrance was large pile of decorated yak skulls. Throughout

Tibet, I would have difficulty coming to grips with the differences between the

beliefs of Buddhism and the Tibetan practice of Buddhism. How do you reconcile

all the idol worship, the killing of animals, and the amassing of wealth all for

a way of living that decries such practices?

Really, I never worked it out, and I emerged from my time in Tibet disappointed

in my ability to connect with Tibetans on a spiritual level. Part of it was

the language difficulties and part of it was the long repression of Buddhism by

the Chinese, but there is a more fundamental issue as well. The lay people of

Tibet live and experience Buddhism on a different level. Pilgrims walking

deserted roads and circumambulating chörtens don't see their actions

in an intellectual, western way. The only know that it is right, and

they throw every fiber of their existence into living as meritoriously as

they can.

Buddhism in a Nutshell

|

May all beings everywhere, with whom we are inseparably interconnected, be

fulfilled, awakened, and free. May there be peace in this world and thought the

entire universe, and may we all together complete the spiritual journey.

|

--Quoted by Surya Das.

|

Warning: I'm not a Buddhist scholar, and I don't intend to play one on the web.

But, Buddhism is such an inherent part of Tibet and the reasons I was there that

I want to try and at least give an impression of the belief system. For a real

introduction

please see any of the many available books on Buddhism. I can heartily recommend

Awakening the Buddha Within by Lama Surya Das, from which I borrow heavily

here.

Buddhists believe we all have the capability for Buddahhood, or enlightenment,

within us. In fact, they say that we are all doomed to being reborn an infinite

number of times in different states until we work our way into enlightenment.

"The Buddha," was an Indian prince named Siddhartha Gautama born

during the 5th century BC. In midlife, he gave up his wife and family to begin a

rigorous ascetic practice. He came to realize this was too extreme a path

and turned to meditation. Eventually realized enlightenment while meditating

under a bodhi tree.

He took the name Sakyamuni, and set himself to showing others how to achieve

this perfect state. His teachings, the so called, "Middle Path," form the core of

Buddhism today. The two central elements are the "Four Nobel Truths" and "The

Eight-fold path"

The Four Nobel Truths

- Life is difficult.

- Life is difficult because we crave inherently unsatisfying things.

- The possibility of liberation exists for everyone.

- The way to liberation is by following the Eight-Fold path.

The Eight-fold path

- Right View

This first step on the Eight-fold path encourages us to see the world as

it really is, without delusions about ourselves. With both our

eyes and our inner sight, The Buddha wanted us to shed expectation and

fantasy to experience what really is around us, be it good or bad.

- Right Intention

The second step on the Eight-fold path is to fill our hearts with empathy and

compassion for all living things, to be completely free from negativity.

Buddhists believe in reincarnation and karma, that our actions in this life

determine how we are reborn in the next. If we conduct ourselves well we will

be reborn in a higher state and eventually work our way into enlightenment, or

nirvana.

In this endless cycle of rebirths, you have been both my mother and my child.

Right intentions teaches us to treat all living things with respect for

this relationship. The mosquito on your arm as been your mother, your father,

your lover, and will be again. Treat it gently, as you yourself would wish to be

treated.

- Right Speech

The Buddha recognized the power of speech, that words can have incredible power

for good or evil. In the third step he directed us to speak only the truth. To

tell things simply and honestly.

- Right Action

|

Do not do anything harmful, do only what is good, purify and train your own

mind. This is the teaching of The Buddha, this is the path to enlightenment.

|

--The Buddha

|

This step on the path commands us to always live consistently with our beliefs.

In all things, to act honestly and well-- not to kill, steal, or bring

disharmony into the world.

- Right Livelihood

Do no harm, act only to improve the world. Right Livelihood encourages us to

think about our relationship with the world and to make sure that it is

healthy and wholesome.

- Right Effort

Living well isn't easy, it's hard and takes continual vigilance. This step on

the path implores us to make the effort in everything we do.

- Right Mindfulness

At this point in the path we need to develop a sense of "nowness," an awareness

of the present. We need to live in this moment, not the past or the future,

and be cognitive of both ourselves and the world around us.

- Right Concentration

Following the path isn't easy, it takes effort and focus. This step on the path

acknowledges that it isn't an easy road and encourages us to meditate and

summon the requisite energy. We need to unify our spiritual aims and then

diligently pursue them.

|

|

- 23 Oct 1999

- Another long day of driving.

Yesterday's environment had been bleak, but we still occasionally saw a band of

nomads herding their yaks and eking an existence out of the barren earth.

Watching closely, we'd sometimes see large rabbits, bigger than the foxes

that occasionally revealed themselves with a shake of a bushy tail.

Wheeling through the high thin air, eagles soared, majestic symbols for this

harsh land. And just as proud, we even saw a herd of wild asses thunder across

the open plain. They kept pace with the Land Cruiser for a while, before

wheeling away and beating out a frothy path towards the northern hills.

Today there was nothing. Just out of Paryang, we made some of the fabled river

crossings, now sedately bridged by modern constructions. But soon there

were no more rivers and no more lakes, and not even the Nomads ply that

territory.

At lunch I tried to joke with Pasang about the possibilities of stopping

at a drive-in, but couldn't make him understand. Probing further I found

that even though he knew all the words to "Hotel California" he had never

even herd of McDonalds! Maybe there is hope for the world after all...

After a full days drive, the first traces of water also brought signs of life.

Eagles and hares, then even people seemed to reemerge as if from hiding.

And finally, coming over a rise like all the rest, the still, cobalt waters of

Lake Manasarovar spilled out across the plain. We knew it must be near, but it

was a surprise even so. Another pile of stones and jumble of prayer flags,

the sort of cairns that seem to mark every obscure corner of Tibet, but

this one marks the spot where holy Mt. Kailash first pokes it's icy head

above the horizon.

It's hard to know just where or when my journey to this point began

but resting in the high mountain air, gazing at the long sought jewel I

contemplate all the circumstances that brought me to this moment and

wonder how this new experience will shape my ever-changing road.

A short drive from Manasarovar is the frontier town of Darchen.

Darchen raises the bar on squalor. The entire town is a minefield of

broken beer bottles, human excrement and unhappy people. It's the

antithesis of all that is Tibet. Pasang has sharp words with some

shopkeepers just trying to get them to boil water for instant noodles,

and then we had a run-in with the hotel managers.

Both hoteliers wanted 120 Yuan for a room not even as nice as the places we'd

been staying. Given that we are the only two tourists in town and the

most we'd previously paid was 40 Yuan, this seemed like outright thievery

to me. I said as much to Stuart and suggested we just start the kora and

sleep on the trail. This incensed the hotel guy and he went scurrying

off to inform the police that we weren't going to pay what we were

quickly coming to see as an informal tax on the kora.

I was all for a confrontation in the name of principle, but Stuart and Pasang

talked some sense into me, and we finally succumbed to this banditry. Welcome

to the holiest place on Earth.

- 24-26 Oct 1999

Mt. Kailash

"Kailash," the western name for the mountain, is so abrupt and jarring.

I prefer the more melodic Tibetan: "Gang Rinpoche" (say: gang

rin-poe-shay). But, the mountain is known by any number of names and

superlatives, mythical Mt. Meru, home of Shiva, "the center of the

universe," "the navel of the world," or, as many westerners know it,

"that holy mountain in Tibet."

With all these labels, the only surprise is how well it fits them all.

Kailash bears an uncanny resemblance to mythical mountains from several

different faiths. It sits alone on the remote Tibetan plateau not the

tallest mountain in this land of giants, but one of the most distinctive.

Its four faces match the cardinal directions and it presides over the

sources of four of the subcontinents major rivers.

The Kailash kora is considered the most holy in all of Tibet. One walk around

the mountain is said to wash away the accumulated sins of a lifetime providing

a clean karmic slate. Serious pilgrims though, will do at least three

laps, or better yet, a more auspicious 13. For the truly devout, 108

koras is supposed to grant instant access to nirvana.

The Tibetan pilgrims usually do the 53km (32 mi) circumambulation in one long

day. Stuart and I will take a more leisure three days, stopping to see

the many sights along the way.

For me, The mountain's initial appeal, was its remoteness and the

difficulty in getting here. As with so many other things in my life, I'd

heard it was hard, so I put it on my list, just another thing to bang my

head against.

But, this journey has been different than most. It's tied to the

transformation of my life and a spiritual exploration. I've come here

looking for something, even if I'm not sure what it is.

|

|

|

Day 1

The day begins with us trying to extract ourselves from the pungent

secularity of Darchen. The hotel people don't recognize a 100-Yuan note,

even though that's what they charge for a room. For a moment, it looks

like we will finally be arrested in Tibet, but finally a more rational

manager is woken to accept our money.

Free at last, we walk past the monastery just outside town, give the prayer

wheels a final spin and head out on the kora.

Less than an hour out of Darchen we get to the first of the four prostration

points that mark the initial views of each of the mountain's faces. Following

the ritual, I prostrate myself here. Facing the mountain, I place my hands palm

together in a prayer gesture, then touch my forehead, mouth, and heart, before

finally stretching myself full length in the dirt with my arms extended.

I feel a bit silly, and I'm nervous about the difference between following a

ritual and mocking it. But in my mind, I too have come as a pilgrim and

this is the smallest gesture of devotion. Hardcore pilgrims will

prostrate themselves the entire way around the kora, making their way one

body length at a time and marking their place each night with a stone.

For the extreme pilgrim, we heard talk of doing the kora while

continually prostrating towards the mountain! That's 53 km through rivers

and over high mountain passes all done by making a prostration then

taking a half step the left and prostrating again. In comparison, my

simple four seem the token gesture that they in fact are.

Our next landmark on the kora trail is the Tarboche flagpole. The tall

slender pole is erected in an elaborate ceremony each spring. The way it

leans is said to foretell the state of things for the year to come.

Perfectly vertical and all is well, towards Kailash and there is trouble,

but not too bad, away from Kailash and it's time to take cover. To our

eyes it seems tipped slightly towards the mountain, and that would seem

to match the general state of things.

Stuart relaxed here while I went to look at the Kangnyi chörten,

just over a small rise. As I approached this rough-hewn arch I flushed

two eagles and watched them pinwheel through the air. As I got closer to

the chörten I saw what had had the eagles attention, fresh goat

heads adorned the arch. I avoided their eyeless stares as I ducked under

the arch to score my Buddhist merit points and again tried to reconcile

my Western notions of Buddhism with its practice in Tibet.

From the gruesome to the macabre Stuart and I then climbed to a sky burial

site. In Tibet, for those who can afford it, the traditional method for

disposing of bodies is sky burial. The corpse is taken to high crag

where it is hacked into pieces and left for scavenger birds. Once the

lammergeyers have carried away the flesh the bones are ground to dust

and thrown in a river.

As we walk through the site I have to choke down an unbearable sense of being

somewhere I don't belong. The cairn dotted knoll is strewn with discarded

clothes, locks of hair and fragments of bone. I picked my way through as

if in a minefield and wonder if I've already stepped on a karmic

antipersonnel device. In the center we come to the rock walled altar and

its collection of well-worn cleavers. Stuart stopped for some pictures

while I quickly retreated to place where the spirits didn't scream quite

so loudly.

Descending from the sky burial site we rejoin the kora trail as it turns down a

beautiful canyon and works its way upstream beneath the west face of Kailash.

The trail is set just above the river and we try to make sense of the waters

murmur as it cascades over the white stones of the riverbed. The walls of the

canyon are painted in shades of red, like something out of the American West.

It's hard to imagine that we are really in Tibet.

The second prostration point is a more meager affair than the first, just a

large cairn marking the first view of the north face. We've settled into

a hiking rhythm, so I take only a moment to make my obeisance, before

carrying on.

The air is thin here and breathing is difficult, but it feels wonderful to

be out in the world after a week imprisoned in the back of the Land

Cruiser. We plod down the trail, with my body on autopilot and my mind is

free to wander.

So, here I am at Holy Kailash, performing one of the most important

rituals in Tibetan Buddhism. I try to meditate and marshal my thoughts

to the task of just being here, in this moment.

In this moment though, my brain is filled with lascivious thoughts of an

ex-girlfriend long gone from my life. I'm horrified, but there is little that

can be done. The harder I push and try to force the direction of my

concentration the deeper it wanders into a wholly inappropriate lurid realm.

I'm hopelessly distraught by the time we get to Dira-Puk monastery, our

home for the night. In this life and others, I've wandered so far and

worked so hard to be here, and this is the best I can manage? I think

dark thoughts and wonder, am I Buddhist? does the question even mean

anything?

|

|

|

Day 2

We wake tired and cranky. It had been a full moon last night, and according to

my readings, we get double-bonus merit points for seeing it here on the

Kora. We kept waking during the night to bundle into all our warm clothes

and brave the bitter night air to check the moon's progress as it slowly rose

over Kailash and ponderously arced over the river canyon.

We'll need that accumulated merit and all our patience though to deal with the

guesthouse caretakers this morning. We had bargained hard with them last night

bringing the price of our bug invested beds and yak dung pillows down from

ridiculous to merely insulting. This morning they are back on ridiculous.

We refuse to pay more than what was agreed to and things start to get very

tense. Voices are raised and angry shouts echo off the holy mountain. In the

end we walk off with them still berating us and we carry large rocks in case

they come after us with drawn daggers.

|

My bodhisattva on duty at the Drölma-la.

|

|

|

Trying to shed that negative tension I throw my energies into the hiking as the

trail begins to climb steeply. Stuart and I have chosen different lines so I

trudge through the crisp clear air with only the company of my bodhisattva.

Bodhisattvas are beings who have achieved enlightenment but instead of entering

Nirvana they have taken a lower rebirth in order to assist the rest of us.

I didn't recognize mine yesterday, at first she had seemed just another of the

mongrel dogs that followed us out of Darchen, but today it seems

obvious that she is to be my guide.

Slowly picking my way up the steep hillside she trots ahead finding the route

and freeing me to explore my thoughts. I resolve to escape yesterday's mental

debauchery and lose myself in the chant of

Om Mani Padme Hum.

Om Mani, as I inhale, and Padme Hum, as I exhale, over and over again, in

and out I make each breath full, swelling my lungs and trying to draw

into myself a bit of the energy I feel about me. I exhale forcefully and

with conscious thought, trying to expel all the emotional ballast that I

want to leave behind here.

I am feeling good as Stuart and I's paths cross and we stop to regroup.

This is the mental state I'd wanted to bring to Kailash. From our rest

point we look down the "shortcut valley." That route is closed to all

who have less than 13 koras so we must continue our climb up towards the

Drölma-la.

Our next stop is Shiva-tsal, a spot on the kora where pilgrims are

supposed to undergo a symbolic death by sacrificing something to

represent what they want to leave behind in this life. I make the

traditional offering by snipping off a lock of hair. Stuart decides to

innovate and leaves behind his boxers to do the rest of the kora commando

style.

It's only a short ways before we start searching for the Bardo Trang sin

testing stone. Tibetan lore has it, that if you can wriggle through the

narrow passage you are not burdened with too many sins as to be completely

cleansed by one Kora. We find the stone and both of us manage to

squeeze through. I wonder if I should try it with my pack though, maybe

some of my sins are in there?

After Bardo Trang, the trail steepens in its assault on the kora's highpoint,

the 5,630m (18,466 ft) Drölma-la pass. All my readings have described the

kora as swarming with pilgrims, but Stuart and I have been mostly alone. It is

after all October, and the weather could turn dramatically bad at any

moment. As we make the long slog up to the pass, I look down to see a

kora-in-a-day pilgrim rapidly gaining on us. The fact that he is

Tibetan, and unladen, doesn't matter to me, my Y-chromosome goes off,

and I crank up the pace.

In the thin air I struggle to breathe and it becomes more difficult to maintain

my Padme Hums. As my breathing breaks, so does my concentration. The pilgrim

is gaining on me, and I curse myself for being slow. Then I curse myself for

caring and finally another curse for caring that I care. I'm well cursed, and

wallowing in a pool of self-condemnation when the pilgrim passes me with a

cheery Tashi Delay. Stuart is far behind, and the pilgrim quickly

ahead. I am left alone to lament my pride and competitiveness, the days

rapture is gone.

It is clear and sunny on the summit of the Drölma-la and the wind is

crisp but gentle as it sends aflutter the thousands of accumulated prayer

flags. I add a string of my own, but not before inscribing them with

the names of my friends and family. If you received a postcard from me

before I left for Tibet, chances are good that your name now flies on the

Drölma-la in endless motion and endless blessing.

As I wait for Stuart, I make a few circuits around the summit stone

chanting the Tibetan pass crossing mantra, Ki Ki so so, La gyalo

(long life and happiness, the gods are victorious).

When Stuart arrives we take a break for lunch and share the tube of

cookies with our ever-present canine Bodhisattvas. The descent is

difficult on my ankle, but

otherwise uneventful. At the bottom of the pass we get to the only one

of the "Buddha footprints" we are able to find on the Kora. These foot

shaped indentations found throughout the region are ascribed to the

travels of Sakyamuni and other saints. This one is atop a large boulder,

so we scramble up to run our hands through the impression of The Buddha's

foot.

The trail is gentler here as it winds down another river valley. Stuart and I

opt for different sides of the river and I again find myself embroiled in a

spurious race. His side begins flatter, and I race up and down the knolls I

find on my shore to match his pace. I'm sure he is oblivious, as I should be,

but I can't free myself from this compulsive competitiveness. I pause only for

a brief prostration at the cairn marking the one glimpse of Kailash's

east face.

I'm frustrated with my own pettiness, but the irritation just spurs me on.

Eventually I wait for Stuart as he has to pick his way back across the river,

and we finish this long day together, making the last easy walk to Zutul-Puk

Monastery.

Here as well, two incredibly annoying caretakers staff the guesthouse.

I'm all for camping in the open, just to spite their extortionate

demands, but Stuart is finally able to knock them down a few Yuan, and we

settle into our hovel for the night.

We boil up some instant noodles for ourselves and the dogs, as they take

up a position on guard just outside the door. Any person or beast

approaching has to withstand a fusillade of barking and it gives us an

odd sense of security in a place where there really is nothing to be

afraid of anyway.

|

|

|

Day 3

|

Milarepa

Famous for achieving enlightenment in just a single lifetime, Milarepa is

one of Tibet's (and my) most beloved Yogi's, sort of a spiritual

all-star.

Once a powerful sorcerer who used black magic to cause several deaths,

under the tutelage of Marpa, Milarepa renounced his evil ways and fled to

the high mountains to contemplate the Dharma.

Living in stark solitude, subsisting only on nettle soup that turned his

skin green, it is said that after years of intense meditation,

he was able to change his body into any shape and to fly.

|

The fear of death and infernal rebirths due to my evil actions has led me

to practice in solitude in the snowcapped mountains.

| |

On the uncertainty of life's duration and the moment of death I have

deeply mediated.

| |

Thus I have reached the deathless, unshakable citadel of realization of

the absolute essence.

| |

My fear and doubts have vanished like mist into the distance, never to disturb me again.

|

I will die content and free from regrets.

This is the fruit of Dharma practice.

|

--One hundred thousand songs of Milarepa

(As found in, Awakening The Buddha Within)

|

In the stories about Milarepa, I find what I expected of Tibetan

Buddhism, a tangle of good and evil, mystical and profane; simple

statements with endlessly tangled meanings.

Surya Das, recounts that when it came time for Gampopa, Milarepa's main

student, to leave, he begged his master for one final lesson. At first

Milarepa refused saying that what was required after all the years of

study was more effort, not more instruction.

But, as the dejected student turned to walk away, Milarepa called out to him.

When Gampopa looked back the master bent over and lifted his robe

to display his weather worn buttocks, callused from years spent

meditating on hard rock. "This is my final teaching, my heart-son," he

called, "Just do it!"

|

|

|

|

Leaving one's homeland is accomplishing half the Dharma

| |

--Milarepa

|

|

|

Zutul-Puk Monastery is built over a cave formed during a contest between

Milarepa and the Bön saint Naro Böchung. The story goes that

Milarepa finished the ceiling before Naro Böchung could erect the

walls. At first the ceiling was too high though, so he stamped it down

with his feet, but then it was too low so he pushed it up with his hands.

The monks here are warm and friendly, nothing like the caretakers, and

they are quite willing to show us the cave. It's a thought filled moment

to crouch in the cave and place my hands in Milarepa's prints. He has

long been my favorite Buddhist saint and I can feel the connection grow

as I ponder his hours of mediation in this very spot.

We are quickly back on the trail, anxious to complete our way

around the mountain. Inspired by Milarepa's cave I vow to be a saintly

model of contemplation today, but it is again not to be.

Over the course of the trip Stuart has adopted the charming Tibetan trait

of spitting, and today it appears he is going to get serious about it.

Step, step, step, hraaawk thpwut!, repeated continuously. I'm yet again

challenged to comprehend the depths of my pettiness, but the fact is, the

spitting is driving me crazy. It just isn't a pleasant sound and each

thpwut! brings me crashing out of my meditation.

I resolve to take this on as a challenge though, to let the jarring wash

over me with no effect. I won't complain, I wont ask him to stop, and I

won't avoid the situation by intentionally rushing ahead. It doesn't

work, I'm seething as I work to focus on my mantras. Thankfully, I'm

saved from my weakness as we develop a natural separation on the rolling

hills, and I again reach for the calm I'd hoped to carry with me all

through the kora.

I miss the official 4th prostration point, and so pick a likely looking

cairn draped with prayer flags. As I rise and turn back to the trail I

see my spiritual guide being sexually assaulted.

What are the lessons in all this? I do not know. I thought I would do the

kora and feel bigger, more powerful, but instead, I feel naked with all

my blemishes revealed.

|

|

- 26 Oct 1999 (contd.)

-

Back in town I made one last circuit around the monastery, spinning the

prayer wheels and trying to sort through my thoughts. The kora

completed, we made all due haste to escape the highly insalubrious environs

of Darchen.

While Lakbha napped Stuart and I got to take turns driving the Land

Cruiser on the way over to Lake Manasarovar.

Manasarovar is one of the holiest lakes in the world, but even in the sun

it was chilly in October at 4,560m (14,950ft) and the slow drop off made

bathing tricky. I waded further and further out before finally giving up

and plunging into the knee-deep water.

|

|

Me, about to wash all my sins away in the holy, but chilly, Lake

Manasarovar.

That's Kailash in the upper right.

|

|

Back on the marshy shore I bottled up some of the water for future sin

cleansing before we headed back to get Lakbha.

While we'd been gone he'd met a friend of his who needed a ride to Lhasa,

and they wondered if we'd mind helping him out. In our newly sin-free

state, how could we have refused? We crammed his bedroll, stuffed full of

his belongings, into the back of the Land Cruiser and returned to the road.

As well as our new passenger we seemed to have picked up a funky odor and at

lunch we discovered what it was. While we waited for our thukba he rooted

through the back of the truck and produced... a sheep carcass. Ahh, I see,

lunch was to be his treat.

- 27 Oct 1999

-

We were up early, and back on the lonely road. We quickly left behind the

pleasant lake region and recrossed the barren valleys. With the high

Himalayans on our right and the rolling hills of Tibet on our left, the

road snaked its way down valley after valley. Each climb to a low pass

revealing another valley and an identical stretch of road.

We made it back to Paryang, and as I went for an evening walk I discovered

our previous footsteps on the sand dunes. The seemed fresh, as if made minutes

ago, not days. And already, I could feel the kora fading into that funny

space between memories and dreams.

- 28 Oct 1999

- Another lonely day of driving, endless valleys and barren hills

dappled with the occasional green bit of scrub. Out of the monotony,

appeared the dust plume of another Land Cruiser. We stopped to chat with

them, another group of tourists on their way to Kailash. We were sad to

lose our title of last in to Kailash that year, but it was a welcome

break and strange really to chat with new people after so long on the

road with Stuart.

One of their group was a woman named Tina. As we talked I discovered she was

from California, in fact she lived in a small mountain town where I have

friends and it didn't take long to come up with a common friend.

Amazing, to be the only two groups of foreigners in Western Tibet and to

discover ourselves friend-of-friends.

- 29 Oct 1999

- Drive, drive, drive!

Back over the pass where our adventure had almost been halted before even

begun, back down the brutal streambed aspiring to be a road and finally back

into Lhatse, a "real" town in our newly skewed perspective.

We celebrated our return to civilization with a meal that, "wasn't noodle

soup," and then went out on the town. The nightlife in Lhatse consists

of one Karaoke place that, as we were to discover, is also a Chinese

brothel.

As with a cup of butter tea, it seems impossible to empty a beer glass in

Tibet. Round after round of 500cc beers was brought to the table despite the

fact that only Stuart and I seemed to be drinking. Every few minutes, one

of the elegantly dressed hostesses would come to our table to lift our

glasses that we were then expected to down.

After a few hours of this, the whole idea of Karaoke didn't seem quite so bad

as when we arrived. Stuart was cautious, because when we'd tried this in Lhasa

they didn't have any English disks and he found himself on stage,

microphone in hand, before a large crowd expecting something a capella.

With Pasang to negotiate they managed to find, "My Heart Will Go On" from

The Titanic. So as Stuart crooned his love song, I got the attention of

one of the hookers and took her out on the floor with the chaste dancing

that seems to be the expected behavior in this sort of establishment.

Hand in hand, but with ample space between us we tread about the floor like

something out of a grade-school dance. But, as Pasang assured me, for

500 Yuan she would go home with us for the night. Not quite ready to

part with my sin-free status I politely declined.

After Stuart's standing ovation of all 8 hookers the cry of "disco" broke

out. This seems to roughly translate as, "please play some real dance

music and not nauseating love songs for pot bellied Chinese businessmen

to serenade prostitutes with." For the record, I'm not a very good

dancer, and this isn't helped by 47 small glasses of beer. It was sad

then to watch these beautiful but unfortunate women stare at the aimless

wanderings of my feet as if the meaning of life might there be suddenly

revealed. If a craze of arrhythmic staggering breaks out across rural

China, I may be personally to blame.

- 30 Oct 1999

- Back in the Land Cruiser, we at least got to drive a new road, this

time towards Mt. Everest base camp. After paying the entrance fee we

climb to the 5,100m (16,728 ft) Pang-la pass. The summit of this pass

looks out on the roof of the world. Dominating the view is Mt. Everest,

but this is the most spectacular point in the most spectacular mountain

range on our planet. Makalu, Lhotse, Everest, and Cho Oyu are lined up

like teeth ready to take a bite out of any adventurer daring to try them.

At 8,848m (29,020 ft), Mt. Everest, the world's highest mountain, sits

right on the Tibet/Nepal border. While I haven't been, I've heard the

views from the Nepal side are disappointing. From base camp you can't

see the summit, only the Khumbu icefall, the first challenging section

of the climbing route. In Nepal, views of the summit can be had from a

nearby trekking peak, but a bit of the magic is lost from that

perspective, Lhotse, Everest's sister peak, looks taller.

There are no such issues on the Tibetan side. Everest, or Qomolangma as it is

known in Tibetan, is clearly monarch in this kingdom of mountain gods and the

entirety of it's 3,000m (10,000 ft) North face springs from the valley

into the heavens, every inch is visible.

From a climber's perspective, Everest isn't really a difficult mountain.

The challenges are posed only by logistics and altitude, the actual

climbing is quite straightforward. Compare this to the 8,611m (28,244ft)

K2 in Pakistan. While 237m (776ft) below Everest, it may be only the,

second highest mountain, but it has extremely difficult and technical

mountaineering it's entire length and a mortality rate that makes a trip

to Everest look like a Sunday outing to the art museum.

Knowing all this, I, like many armchair mountaineers, had always

considered Everest to be a "tourist mountain" that I really couldn't be

bothered to climb even if the permits weren't so ridiculously expensive.

Standing in Tibet though, looking out at the north face, all that

changed. It's a beautiful mountain and the northeast ridge is a

spectacular and aesthetic line. Qomolangma captured my heart and my

imagination, and the wheels began to turn in the back of my mind.

n.b. In Nepal, my camera containing all my film from this

region was stolen. You, like me, will need to make due with just my memories of

the moment.

On the other side of Pang-la pass we found the worst road yet. It was poorly

graded, badly rutted and full of boulders. It took all of Lakbah's

concentration to just creep along at a walking pace. Beyond the painful decent

though, we found a pretty little valley full of interesting Tibetan towns.

As we wound through the villages we got glimpses of rural Tibetan life.

We watched as they tilled fields with yak-drawn wooden plows and threshed