|

|||

| Four inch anti-aircraft gun on the HMS Repulse. |

I confirmed my ersatz buddy agreed with this, then rapidly clipped my camera and tank of decompression gas to the line I would trail behind me into the wreck. A final forlorn glance from Tim and I wriggled through the hole and up into the wreck.

The entrance must have been an ordinance hatch because inside I found a

tangle of heavy equipment designed to load and transport the ship's

mammoth 15-inch shells. Struggling to orient myself in the upside-down

battle cruiser I carefully wound my way through the machinery vainly

trying to arrange my guideline so that it would be safely navigable in

the absolute darkness of a silt-out or torch failure. Squirming through a

final small gap in the Rube Goldbergian mechanism I won through to a

corridor and followed it deep into the ship.

|

|||

|

I carry decompression plans for several different bottom times. These

sets of carefully timed stops at ever shallower

depths and breathing increasingly oxygen rich gas mixtures will allow the

excess nitrogen and helium to safely off-gas. If after my planned bottom

time of 30 minutes I was to ascend directly to the surface without doing

these stops my blood would froth and boil like a violently shaken bottle

of soda. Assuming of course that I can find my way outside the wreck to

begin with.

|

|||

|

Even my own breath is potentially fatal. The bubbles I exhale could dislodge debris from the ceiling, at worst causing a complete collapse and at a minimum stirring up silt to the point that even with a torch there is absolutely no visibility. In a silt-out the idea is to follow the line by touch to the exit, something that sounds eminently practical when read from a book, but is fabulously difficult in practice.

Gliding down the corridors of this once mighty warship my thoughts wander

to just how alone I am. Even without any sort of problem, I stirred

the silt up quite badly working my way through the wreckage of the shell

transporter. On my way out I'll have to negotiate that bit by feel,

inch by inch, being cautious not to gash myself or my equipment on the

innumerable sharp edges. This delicate operation must be done in

absolute blackness while maintaining control of my buoyancy and keeping

track of the time and my gas supply.

|

|||

|

The fact that my dive has been carefully planned and that I am properly trained and equipped does little to allay the knowledge that I am far out in harm's way, albeit not quite as far out as were the original Force Z sailors.

The British battle group known as Force Z consisted of the battle cruiser Repulse and the battleship Prince of Wales as well as the escort destroyers Tenedous, Electra, Express and the Australian man 'o war Vampire. On December 10, 1941, just a few days after the American debacle at Pearl Harbor, Force Z came under intense attack by Japanese bombers.

At 11:18 the first wave of high level bombers came over the fleet.

There were a few minor hits, but nothing like what was to follow.

Subsequent waves of torpedo bomber attacks proved devastating. The

Prince of Wales was quickly disabled, one of her propeller shafts

bent and the steering mechanism disabled.

|

|||

|

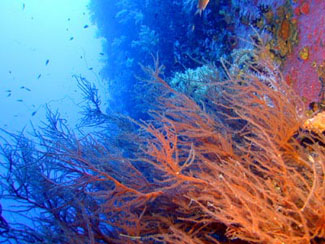

Coral on the hull of the Seven Skies.

|

By this time the Prince of Wales had taken six or seven torpedo hits and was probably already doomed, but a final flight of high level bombers delivered the killing stroke. At 13:25 the great ship capsized and sunk with 327 men still on board.

In current day Britain, diving these wrecks and other so-called "war graves"

is a contentious political issue. On one side are veteran's groups who

are justly unhappy about the idea of divers rifling the wrecks for

souvenirs. On the other side are responsible divers who come with a

"take only photos leave only bubbles" ethic and are enthralled by the

history and challenge of diving these wrecks. Between these two

extremes are all manner of scalawags, ranging from the sport diver on the

look out for the occasional artifact to commercial salvagers who have

gone so far as to remove one of the Repulse's screws for scrap.

|

|||

|

Swimming down the corridor of the overturned ship I frequently check my gauges and note that my "one third of gas" turn around point is approaching. As I begin mentally rehearsing my exit I shine my torch forward for one last look and am startled to discover the largest moray eel I've ever seen poking out from the wall.

Morays are generally shy and non-aggressive, but this one is as big around as my thigh and in the tight confines of the ship who can tell. With forward passage blocked and with my turn point imminent, I quickly spin around in the corridor and begin reeling myself in back along the line.

Everything goes smoothly and the silt has even settled somewhat as I retrace my path through the shell loading equipment. Back outside the wreck I breath a sigh of relief even though my accumulated hour of required decompression time is just as dangerous a ceiling as the steel walls of the wreck. With my camera and tank of decompression gas quickly retrieved I have a few minutes to wander the keel of the ship. Surveying the torpedo damage I'm surprised to discover a napping sea turtle, seemingly an awfully long ways from any sand in which to bury eggs!

Many technical divers have their own way of whiling away the time at decompression stops. My old trimix instructor, John Bennett, brings down sections of paper back books and then sets the pages adrift as he finishes them. I usually spend the time in quiet contemplation, reviewing this dive, and planning the next one.

We began this trip on an unidentified wreck. It's suspected to be a

British oiler but there is no record of its loss and so far no

identifying markings have been found. Other than the mystery it's an

unremarkable ship and the visibility wasn't great for our dives, but

it made for good warm-up dives, a chance to settle in to the twin tank rig

before the longer penetration dives to come.

|

|||

|

I thought the diving here was excellent. On our first dive we dropped into the engine room which is absolutely mammoth, several stories tall and filled with all manner of heavy machinery on a Brobdingnagian scale. Of particular interest was one of the huge boilers crushed like a tin can by the pressure at 45m (150ft).

On our second dive we toured through the crew's living space. Room after room of shelves still chock full of everything needed to venture out on the sea for weeks at a time. We even found some sort of locked equipment cage, or maybe a bursar's office? There is always an eerie feeling touring these now underwater living spaces, a sense that time has stopped and frozen everything in place, just waiting for the crew to return.

From the Seven Skies we moved to the Battleship Prince of Wales, sunk in the same battle as the Repulse. The Prince of Wales lies in 70m (230ft) feet of water. At that depth the amount of oxygen in normal air is toxic, so the wreck is best dived hypoxic mixes of gas. Because of this added complexity and expense she is infrequently dived and I was quite excited about the opportunity.

Like many top-heavy battleships she has sunk upside-down, but luckily, with a

slight lean so that amidships the deck on one side is a few meters off

the bottom. Sadly, we wasted a lot of air trying the wrong side first,

so that by the time we found the gap there wasn't enough gas left to

attempt a penetration.

|

|||

|

At the Repulse was another dive boat on an expedition sponsored by the British military. There had a film crew aboard that seemed to devote an awful lot of attention on us, presumably to be cast as the villains in their documentary? Their ostensible objective was to lay wreaths and plaques and to conduct a general survey of the ships condition, but, the scent of boondoggle was in the water as all I saw them do was zoom around in circles on underwater scooters.

For our part, we did a dismal job of acting villainous as my dive

buddy, Steve, was a Veteran of the British service and brought an ensign

of his own to leave on the wreck.

|

|||

|

The current was ripping at the submarine and here I had my only incident of the trip. I rounded the bow of the submarine running low on both planned bottom time and air, but I misjudged the distance to the tag line that would lead me to my planned ascent route, up the ships anchor line.

I ascended up through the thermocline to where I could see the anchor line, but there was no way for me to reach it in the strong current. A problem, but one I had plans for dealing with.

Using my reel I launched a surface marker buoy to the surface alerting the boat crew that I'd be doing a drifting decompression and giving me a support to maintain the precise depths required.

I'd been planning to decompress with 100% oxygen supplied from boat, but

now I would have to do a longer series of stops using only the 50%

oxygen I carried with me. After more than an hour of decompressing in

the current I surfaced miles from the boat and was thankful that my

buoy had been quickly spotted and a dingy sent to drift with me.

A demonstration of the importance of backup planning, and a shaky

end to and otherwise great trip.

I suppose there are those who will never understand why divers would want

to take on the risk and expense of visiting deep wrecks, but for me it is

the best sort of diving. At ease with my equipment, experience and

training, I get to visit sites of great beauty and history. That people

have died on these ships is a sad fact, and I myself have no intention of

disturbing their rest. But how better to remember them and the reasons

for their deaths then by visiting the site of their legacy on the bottom

of the sea.

| ||

|

Nets shrouding the unknown British oiler.

|